Consciousness and Memory:

Which Comes First?

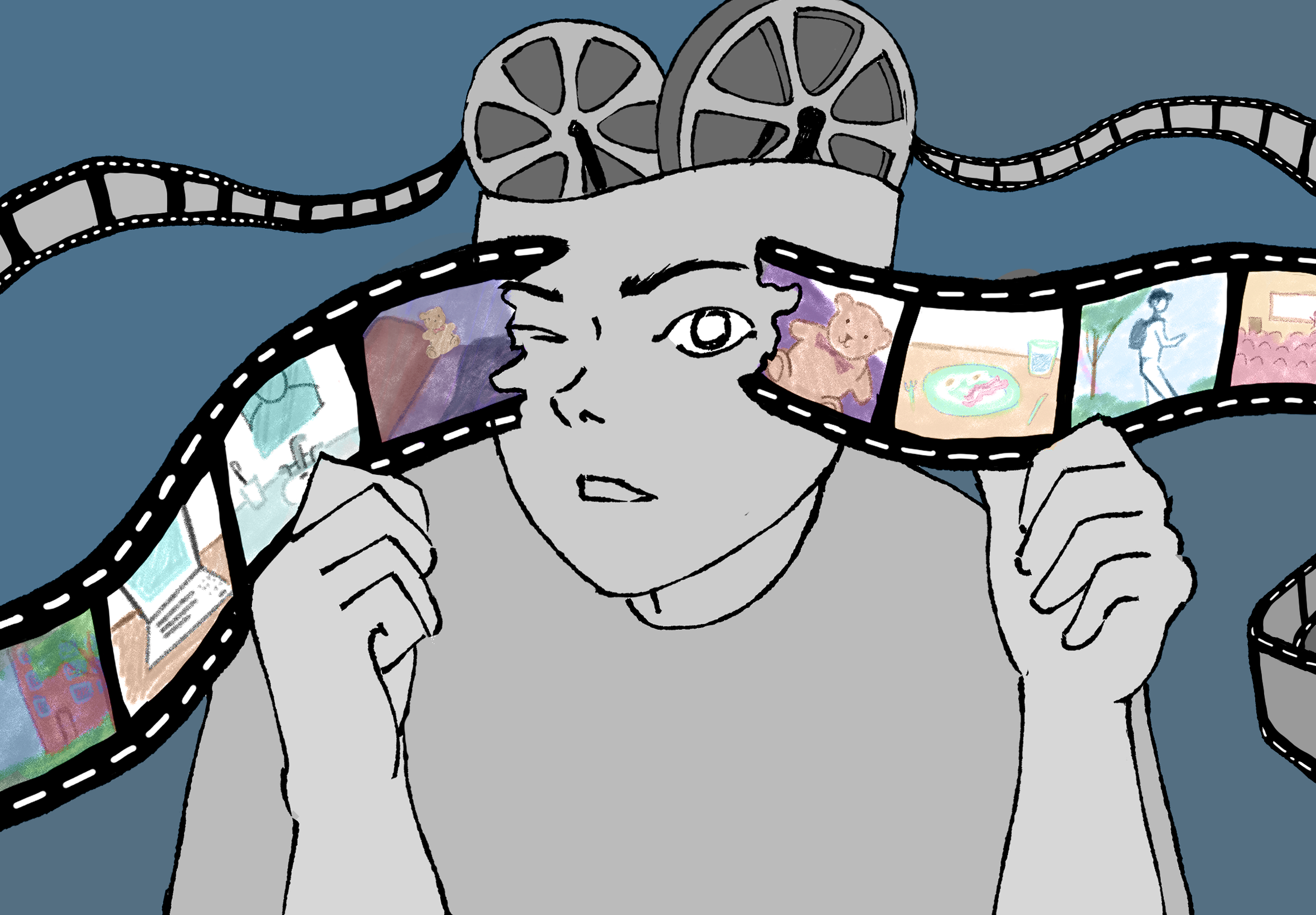

The brain’s narrative construction of our consciousness poses questions for what it means to have memory in the first place

Written by: YJ Si | Edited by: Morgan Nguyen | Graphic Design by: Dora Meiwes

Imagine you have been injured in a terrible accident and have suffered severe brain damage. Fortunately, you survive with no paralysis, but you can no longer create new memories. You can continue to interact with the world, but you cannot encode these experiences into long-term storage. You wake up each day as if it were completely new, with no recollection of anything that happened after your accident.

A situation like this is often the plot of a lame movie or novel, but it strikes a critical question about the human experience: what does it mean to be conscious? Why are we conscious?

It is first important to define terms. “Consciousness” is the unified, “live” experience by which you are reading this article. “Memory” is defined specifically under what psychologists call “episodic” memory; that is, the long-term storage of previous experiences that can be recalled and re-lived like an episode of a TV show.

To answer our questions, we will first look to a mostly unconscious experience: sleep. Research (and personal experience, likely) has shown that we are incapable of remembering events which occur roughly 4 minutes before we fall asleep. If you were reading a book before you went to sleep, you might notice the next morning that your bookmark is well ahead of what you actually remember reading. We know our experience must have been continuous, that there was a period of time in which we were not asleep, but we have no memory of that experience.

We sleep in multiple stages, one of which is Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep, where our dreams tend to be more bizarre, lengthy and emotionally intense. If that’s the case, there are clearly gaps in our sleep where we don’t dream, and yet we also cannot perceive those gaps; the brain fills in the rest.

Experiments have also shown what are called postdictive effects—our conscious experience of the world can change based on information that occurs after that fact, suggesting that our experience of the world is not “live,” but a greatly complex construction by the brain of varying sensations that then becomes what we call our experience.

One example is the color fusion effect. In this experiment, a red disk is presented for 40 ms, immediately followed by a 40 ms green disk in the same spot. The percept is a single yellow disk, rather than any red or green, meaning that the visual perception of this disk must have formed after the initial sensory inputs.

But what’s the relation of this conscious construction to memory? One theory suggests that this development of consciousness and memory necessitate each other—consciousness developed in order to allow episodic memories.

Endel Tulving described three requirements of memory storage: (1) encoding: creating a mental representation of a moment, (2) consolidation: storing the representation in some lasting form, and (3) retrieval: reflecting on the representation at a later time.

Andrew Budson suggests that for these stages of episodic memory, conscious experience “binds” elements of an experience together, like compressing a massive dataset into one holistic experience. This single experience makes it possible to “recall” the unified experience rather than countless sensations/data points. According to this theory, with access to memory and the ability to draw from past experiences, our evolutionary success became much higher.

We can see here that there is some relationship between consciousness and memory that is critical to understanding the nature of what it means to be alive as a human. But there are still more questions about the implications of this link for what it means to exist.

What does it mean that our conscious experience is not immediately or even accurately experienced? This has implications that might change our understanding of free will, of the “self,” and of our life on Earth. Nevertheless, these new theories are exciting ways to think about our place in the universe as intelligent organisms.

These articles are not intended to serve as medical advice. If you have specific medical concerns, please reach out to your provider.